Current Freed-Hardeman student Clifford Blake Griswell is a former U.S. Army Ranger and member Delta Force (SFOD-D). Enrolled in FHU’s cybersecurity program and double-majoring to get his bachelor’s degree in psychology, he previously received his A.A. in Psychology from Sandhills Community College in North Carolina. With a B.S. in Cybersecurity, Griswell hopes to work with the federal government as an ethical hacker or in penetration security. He transferred to FHU after talking with President David R. Shannon about the new cybersecurity program, and the idea of double-majoring in psychology and cybersecurity appealed to him. Several compelling events and experiences brought him to FHU.

The youngest of nine children, Griswell was adopted by John and Sadie Beachy when he was an infant. The Beachy family had an Amish background and was originally from Delaware. His biological mother met the Beachy family through their fruit and vegetable sales, and they began babysitting Griswell. In time, his birth mother and the Beachys agreed that the family would keep him permanently, and that his birth mother could see him whenever she wanted; there were no formal adoption papers involved. Griswell learned of his legal last name when he was 13 when he saw his biological mother on his birthday.

“I don’t think I could’ve asked for a better childhood, and I remember it like it was yesterday,” Griswell said.

Griswell attended Finger Christian Fellowship every Sunday and was part of the school held in the church’s basement from first until seventh grade. When he completed seventh grade, the teacher gave him a certificate, and he went straight to work helping his family on the farm or at the sawmill. At 12, he helped his father build Grandma’s Home Bakery, now known as Ada’s Country Store. Every night, the Beachy family gathered around the dinner table for family devotions after supper. Each morning before school, he would be up with the rest of his brothers and sisters at sunrise helping milk the cows or feed the chickens.

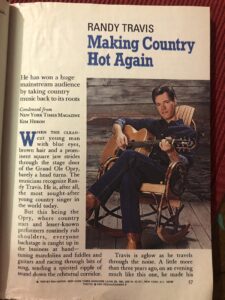

During his free time, Griswell would go to the woods to build cabins and play Davy Crocket. He had a number of unique pets throughout his childhood, including two wolves, a raccoon and two crows. He trapped and hunted and helped at his parents’ sawmill in Finger, Tennessee. Though he was too young to work at the time, he remembered watching his dad make wood furniture. Once, John Beachy sold a dozen hickory rocking chairs to Randy Travis.

“My dad didn’t know who it was at the time, but he came home one night and said, ‘Praise the Lord. We sold all the rocking chairs,’” Griswell explained. “He took all these rocking chairs to Nashville for a craft show, and he met this lady named Liz, who was actually Randy Travis’s manager. She asked if my dad would make some rocking chairs for Randy and his wife. He told her he would, and he delivered them personally to Randy Travis’s cabin.”

Beachy recounted this story to his family later that night around the dinner table and concluded it by saying casually, “I think his name was Randy Travis.”

“See, we didn’t have any radios. We had alarm clocks, plumbing, electricity and a couple of cars, but no TVs or radios. I do remember around the time I was six or seven that one of my brothers’ alarm clocks had an antenna on it. Well, my brother turned that radio on to 104.1, and it was ‘Diggin’ Up Bones’ by Randy Travis! It was the first song I ever heard! I got chills all over listening to that.”

Randy Travis was featured in a 1989 issue of the Reader’s Digest, with a photo sitting on the front porch of his cabin in one of the rocking chairs that Beachy had made and sold to him.

When Griswell turned 15, he moved to Oregon to live with another Mennonite family for two years. After meeting his biological mother on his 13th birthday, he felt confused and wanted to get away for a time. He purchased a plane ticket and flew across the country.

While in the Pacific Northwest, he spent much of his time working at his host family’s seed factory. He rode dirt bikes after work, watched Bruce Lee movies, and was issued his first driver’s license. At one point, he contracted monoclonal spinal meningitis. According to the doctors, the illness might have left Griswell in a comatose state for the rest of his life. After spending a week in the hospital, however, he proved the doctors wrong, making a full recovery and going back to work at the seed factory.

When Griswell was 17, he returned to Chester County for his birth mother’s funeral. He decided to stay in Finger and return to work with his adopted family in the logging industry.

One evening while in Jackson, he came across a Ninjutsu class in progress. Looking through a window from outside the building, he watched the teacher and a handful of students train and practice various close quarter knife fighting and defense techniques. Watching Bruce Lee movies in Oregon had piqued his interest in martial arts, so he began planning to take the classes himself. After a few weeks of watching through the windows, he worked up the courage to enter the Ninjutsu class. He immediately turned to leave, but the instructor met him outside and urged him to join the class.

“I asked my sensei if we could go off and learn on some deserted island or something,” Griswell said. “I didn’t want anybody to know I was doing it. To this day, my mom and dad don’t know I took Ninjutsu. I just recently told one of my brothers.”

For six days a week, Monday through Saturday, Griswell would spend his late afternoons and early evenings practicing and learning martial arts. To keep his family from learning about his Ninjutsu classes, Griswell would wash his gi at his sensei’s house and leave it there for class. By the time he stopped taking Ninjutsu, he had earned his third degree black belt. His sensei was a former U.S. Army Ranger, who had served in the Vietnam War and was a “tunnel rat” — a soldier who cleared tunnels dug into the jungles and hills by the Vietcong. He passed down the experiences he learned during the war to his students and trained them in close quarter combat and defense.

During his Ninjutsu classes, his sensei began to tell him about his service in Vietnam, as well as his time spent with the Rangers. He encouraged Griswell to join the Rangers, saying that he believed that he had what it took to serve in the military.

It was during this time that Griswell began searching for something else to do for work. “I still wanted to do the most dangerous stuff, and I was getting my license in welding. I wanted to work in underwater welding because it was up there in the top five dangerous jobs,” Griswell said. He underwent a physical for the welding company he was to work for, and they sent him a plane ticket to fly to the coast to work on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

The next day was Sept. 11, 2001. It began as any other day for Griswell. He didn’t fully grasp what was happening in New York or Washington, D.C. at that time, but he arrived at his Ninjutsu class, where his teacher immediately told him, “We’re under attack and being invaded. You should join the Army. You need to be a Ranger.”

“I don’t know if it was to prove to myself or if it was some drive. I wasn’t trying to show off to my family; I just wanted to do it, so I decided I wanted to be a sniper,” Griswell said. “I could shoot pretty well, so I dropped my flight to the coast, dropped my job on the oil rig, and I went to the recruiter.”

At the time, all Griswell had was the certificate he received in seventh grade. He went to the recruitment station at the mall in Jackson. “There were so many choices with all the branches, so I just started on one end and worked my way down the line.”

He went to the Navy and told the recruiter that he wanted to be a SEAL, but the Navy recruiter laughed at his seventh grade certificate and told him they wouldn’t accept it. Griswell would return later after passing his GED test, but, once again, the Navy recruiter turned him down and told him they didn’t accept GEDs, either. He went to the Marine recruiter next and told them he wanted to be in Marine Recon, but the recruiter turned him away for only having his GED. Griswell skipped the Air Force, thinking that if the Marines wouldn’t take him, then neither would they. He went to the Army recruiter and told him, “I want to be what Rambo was.”

“Rambo was a Green Beret,” the recruiter informed him.

“Oh, I don’t want to be that,” Griswell responded, but he still enlisted with the U.S. Army after taking his ASVAB. He scored 110 on the test, and, at the time, didn’t realize how significant it was. It opened a door for him to attend any special operations school he wanted. He went through basic training, which was very hectic in the post-9/11 military.

In his early days with the Army, Griswell attended sniper school as a private first class. During the Invasion of Iraq in 2003, he was part of a sniper team directly under the command of General Petraeus in the 101st Airborne Division.

“While I was overseas, I saw these guys flying around in Little Birds, and I said, ‘Oh look at those Little Birds up there.’ ‘That’s Ranger Battalion,’ someone told me, and I knew I wanted to do that,” he said. “If I keep moving forward, I’m just going to keep going until something tells me to stop.”

He was always one of the first to volunteer for any military schools or training instead of going on leave. When Griswell returned from his first deployment in 2004, he volunteered for Ranger school. After his training was completed, he deployed to Iraq again for another year with the 101st Airborne Division. Upon his return, he was assigned to 1/75th Ranger Battalion, in Savannah, Georgia. During his service, he completed several deployments in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

“As a Ranger, most of our missions were at night, so we slept all day and completed two or three missions a night sometimes,” he explained. “There were some deployments where we were doing over 100 missions.”

During one deployment, Griswell was awarded a Purple Heart after receiving wounds in Iraq. They left their base one night on a mission to track down a man who was making homemade explosives. They found the house where he lived, but their target managed to slip away and hide out in a cave. Griswell’s teams searched the cave, along with a bomb dog, Duke, and his handler, May.

The assets that his team was working with believed that there was nothing in the cave, but Griswell ordered his two teams to set up and begin searching the area for their target. A sniper that was attached to the team only searched halfway down through the cave before thinking that there was nothing else down there and headed back out.

“While my two teams were out looking for holes in the cave, I ended up taking myself, the dog handler, May, his military working dog, Duke, my first sergeant, and our battalion physician. I don’t know what our physician was doing there, but it was probably a good thing he came with,” Griswell remembered with a chuckle. “I was the last one coming back up after checking the cave. Duke, I’m for sure, ended up saving our lives. It was about halfway up, and we were struggling to get out of the cave.”

The dog, Duke, sat down near the cave wall and began growling and circling close to where Griswell was standing. He checked on the dog through his night vision optics, and he knew that something was wrong. He radioed to May and informed him that the dog was acting out of his normal pattern. They let the dog go and watched Duke start scratching at the cave wall. Through their night vision optics, the cave wall appeared smooth. A big rock fell out of the mouth of a smaller cave and rolled down toward Griswell.

“That’s when I saw him inside there. He had probably five or six grenades on him and started dumping them out. I took the guy out, but he managed to blow everything up,” Griswell said. “And underneath me, the guy had actually buried a bomb too deep, and it didn’t go off. I got blown back about 20 feet, got shrapnel in my left side, and I’m deaf in my left ear. May got shrapnel in his back, Duke had to have surgery on his right leg, the first sergeant had shrapnel in his neck and blood was squirting out. We all got injured, but we all made it. It all happened so fast; it was over in about 30 seconds.”

Even after earning his Purple Heart, Griswell continued to deploy to Afghanistan and Iraq with 1st Battalion. Because many of their missions took place during the night, he and his men would sleep during the day. They passed what free time they had by going to the gym to work out, eating or playing video games against other squads.

“It’s so funny, you know? We’d be playing Call of Duty some days, when we’re actually over there doing it,” he said. “We’d come back from showering and the gym, and the whole squad would get together and play against another squad in Call of Duty or Halo.”

In 2010, Griswell was stationed at Fort Bragg among their very small community of special operators who are part of the renowned Delta Force. At the time, he had no intentions of getting out of the military and planned to retire from Delta, but 15 years into his service, things began to change.

“I was right in between signing my last indefinite reenlistment that would’ve kept me for 22 years, so I was going to retire from Delta,” Griswell explained. “When you’re in something so deep and so fast and you think you’re doing really good and you know you’re doing really good… it’s like God had an intervention with me to stop me, but it was causing me to see that I was gonna fail with my job and my position. Then my goal became to stop with the military. From the end of 2014 to 2016 were the worst years of my life. My mom, Sadie, died of cancer in December 2015, and John died four months later. My sister, Linda, died of breast cancer in June that same year. That all happened within a year, and the whole time, my wife and I were going through a divorce. We were fighting back and forth for custody of my three boys.”

It became a turning point for Griswell. He realized that if he stayed in, he would have completely lost his sons. He understood that he would not be fit for the team and in the right place mentally for the missions if he were to completely lose his family. In 2020, he chose not to reenlist and returned to Chester County, Tennessee, to spend more time with his boys.

“For the first couple of years, it was really bad. I was losing my team and my buddies. I had to put my guns down, but everything happens for a reason,” he said. “I don’t regret anything I ever did in the military. I did everything I was supposed to, and it all worked out in the end.” When Griswell officially ended his military career, he had risen to the rank of sergeant first class.

Today Griswell continues working with the military as a civilian contractor, teaching and training soldiers and operators. He has stopped searching for the most dangerous jobs, but he still enjoys jumping out of perfectly good airplanes and parachuting with his old battle buddies. To begin his next journey, he plans to graduate from FHU in May 2024 with bachelor’s degrees in cybersecurity and psychology.